What is the King’s Speech for and what happens behind the scenes? From hostages being taken to bomb checks, here’s what you need to know.

A new era in parliament has begun with the King’s Speech, giving us the chance to see some of the country’s long-standing traditions.

The speech at the State Opening of Parliament marked the formal start of the parliamentary calendar and brought together the monarchy, the House of Lords and the House of Commons for a bit of pomp and ceremony.

It may have felt like a fresh start but the ceremony was filled with rituals that go back over 500 years.

But what is the King’s Speech for and what quirky traditions are included?

From doors being slammed to bomb checks, here’s what you need to know.

What is the King’s Speech for?

Although it’s the monarch who delivers the speech, it’s the government that writes it, with the aim of outlining its policies and proposed legislation for the new parliamentary session.

While a parliament – meaning the period of time between general elections – can last for up to five years, a new parliamentary session is normally launched annually.

The one before this, which the King delivered for Rishi Sunak’s government, took place in November last year, but this one introduced the new Labour government’s agenda.

Although it’s a formal-feeling affair, there isn’t anything legally binding about the King’s Speech. It can outline bills that never actually become law, and bills can also be passed by the government later that weren’t included in the speech.

Rather, the speech is essentially a giant press release for the government to outline its agenda clearly – and it gives its opposition the chance to criticise it.

How does it play out?

The King leaves Buckingham Palace in his state coach late morning, making his way to the Houses of Parliament in a procession led by the Household Cavalry, which consists of the two most senior regiments in the British Army: The Life Guards and The Blues & Royals.

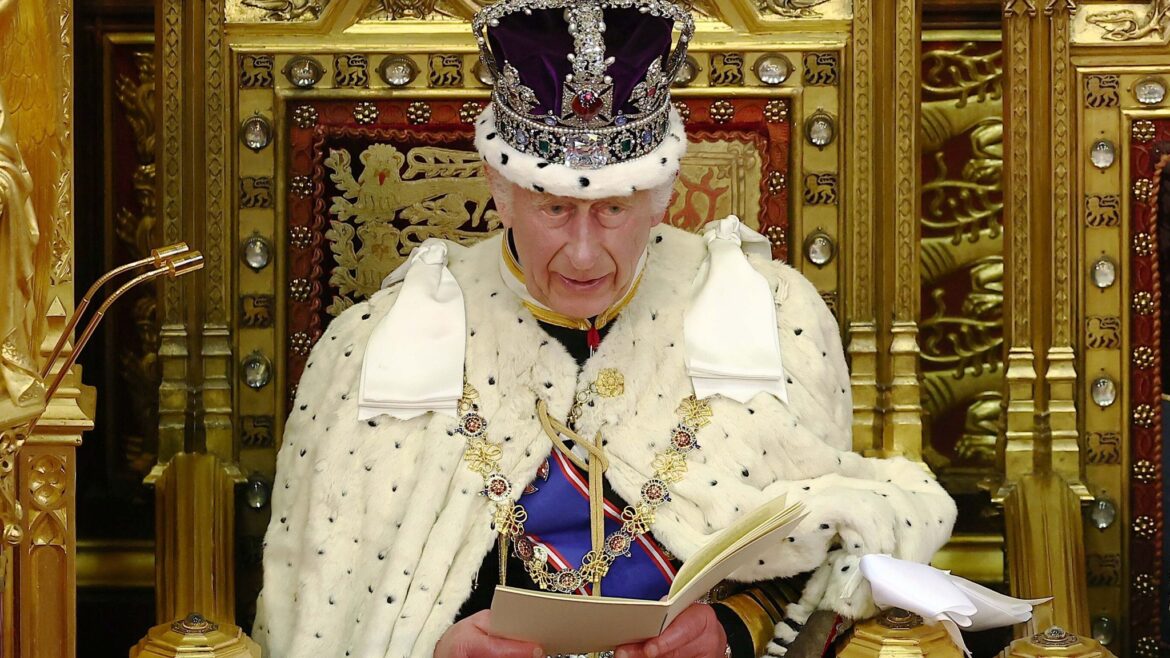

He arrives at the Sovereign’s Entrance at around 11.20am, before heading to the Robing Room to put on the Imperial State Crown and ceremonial robes.

The King then leads the Royal Procession through the Royal Gallery to the chamber of the House of Lords before taking his seat on the throne, where he delivers his speech from around 11.30am.

While there’s no set time for the speech’s duration, outlining a government’s agenda can be time consuming – it often clocks in at around the 10-minute mark.

Once the King’s Speech concludes, a new parliamentary session begins, with MPs debating its contents around two hours later in the Commons.

Debates over the speech typically continue for several days, before it’s voted in by the Commons. The vote is largely symbolic, and no government has lost it for 100 years.

The debate has already been added to the parliamentary diary until Tuesday 23 July.

What traditions do we see?

There’s a few moments that you don’t see every day in parliament, one of the most well-known being the Black Rod’s role.

After taking to his throne, the King signals for the House of Lords official to summon MPs from the House of Commons.

Black Rod obliges, only for the Commons door to be slammed in their face upon arrival. This tradition, which dates back to the Civil War, is used to symbolise the Commons’ independence from the monarchy.

Black Rod bangs on the door three times with their rod before it is opened and then all MPs follow them back to the Lords to hear the speech.

This tradition was born from the monarch’s clashes with parliament centuries ago, particularly under the rule of King Charles I, who was beheaded in 1649 at the conclusion of a civil war caused by the tensions.

Once the members are in and the King is ready to speak, the Lord Chancellor gets down on a bended knee in front of him to present the monarch with the speech, carried in a special silk bag.

As well as the King wearing his crown and robes, members of the House of Lords wear traditional parliamentary robes.

Earlier in the day, the mace – a parliamentary symbol of royal authority – is transported to parliament in a separate carriage. Tradition dictates that without the mace, a silver gilt ornamental club of about five feet in length, neither house can meet or pass laws.

Bomb checks and hostage taking

Two of the most bizarre traditions take place behind the scenes of a State Opening.

Before the monarch arrives at parliament, the Yeomen of the Guard, the royal bodyguards, carry out a search of the cellars of the Palace of Westminster for explosives.

It’s a ceremonial search dating back to the King’s Speech in 1605.

Read more:

What we can expect from the new government’s first 100 days

MP forced to swear into the Commons for second time after using wrong wording

Then monarch King James I, a Protestant, had cause for concern in the aftermath of the Guy Fawkes gunpowder plot – a failed attempt by English Catholics to blow up both him and parliament.

Another tradition to assure the monarch’s safety was introduced in 1649 and sees a Member of the Commons “taken hostage” in Buckingham Palace while the King or Queen attends Westminster.

This again relates to when the monarch and parliament’s relationship was more fractured, meaning the King wanted assurances that he wouldn’t be harmed while in Westminster.

The hostage is usually a government whip. This year it was Samantha Dixon, Labour MP for Chester North and Neston and Vice Chamberlain of HM Household.

Last November it was her predecessor Jo Churchill, who was MP for Bury St Edmunds at the time.

Speaking in a video on X shortly after that speech, she said: “I had an interesting role here in today’s proceedings. So you may have seen that somebody gets taken hostage – that was me.

“So I am whisked away, up to Buckingham Palace, while the King is here in parliament, delivering the speech to both houses. Now luckily, I’ve been sent back.”

What was in this speech?

There were 40 bills outlined by the King in the latest speech, with the focus largely on improving living standards by driving economic growth, the first of Sir Keir Starmer’s five “missions for national renewal”.

Big ticket items included a plan to build more houses and infrastructure, nationalise the railways and give greater powers to the UK’s fiscal watchdog over spending commitments.

Leave a Reply